KEY CONCEPT

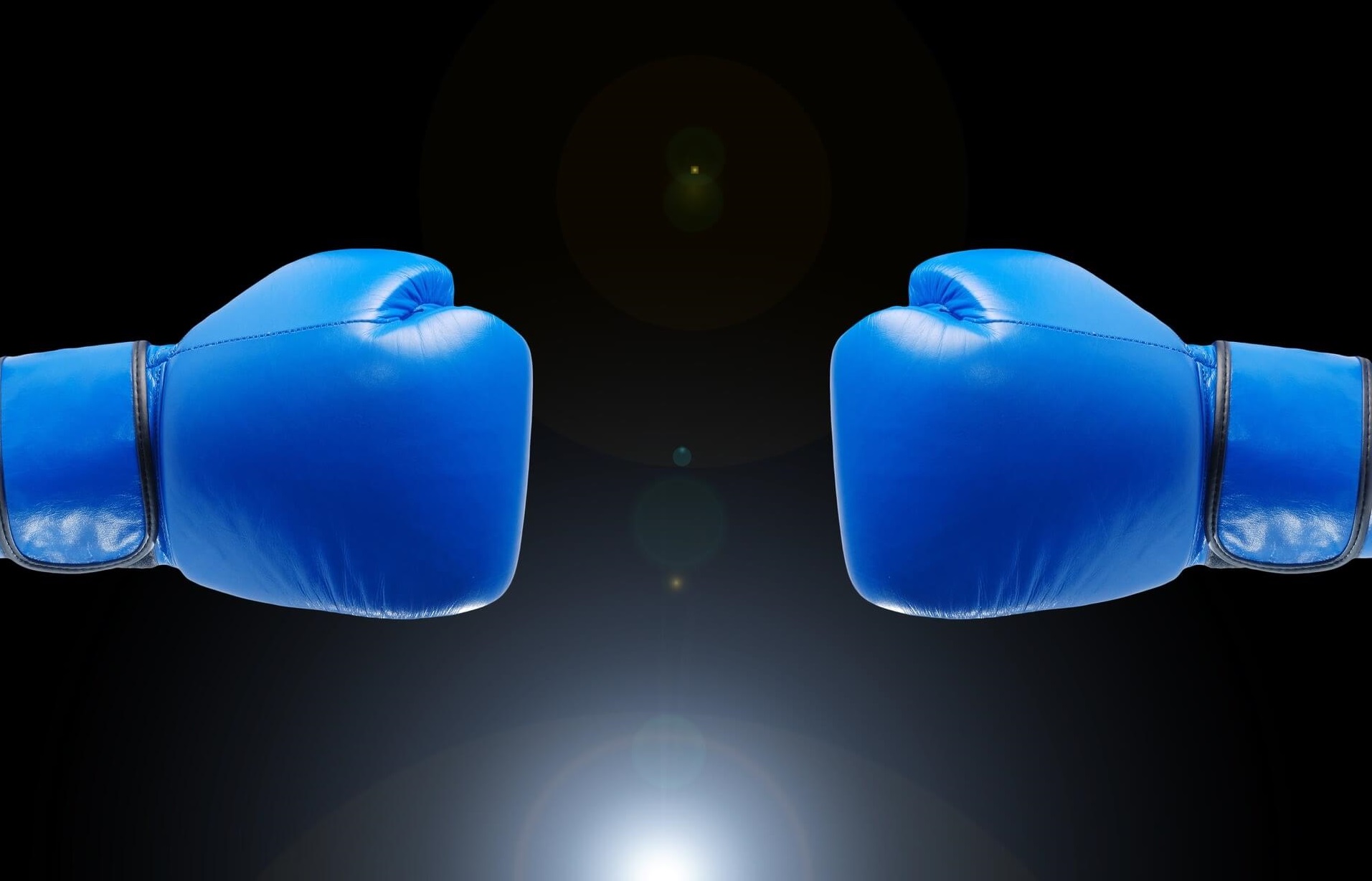

While competition between individuals is a fact of life in the world of business — people vying for that newly opened promotion, for example — a recent study explores the conditions that can turn healthy competition into dangerous conflict.

IDEA SUMMARY

Competition is often a catalyst to productive work. Just as competition among companies spur them to design superior products and offer superior services in an effort to gain competitive advantage, individuals can respond in the same way by increasing the quality of their work and increasing their results in order to “win” whatever the competition might be: a promotion, more funding for their projects, attention from the C-suite, etc.

There are times, however, when competition between two individuals can escalate into unproductive, and even dangerous, conflict. The danger can range from unproductive behaviour (e.g., exchanging insults) to unethical behaviour (e.g., sabotaging the work of the other individual) to physical attack.

A recent study used the history of Formula 1 racing from 1970 through 2014 to analyse under what conditions structural equivalence escalates competition between two individuals into conflict.

Structural equivalence refers to people who would have the same relations with the same third parties.

For example, there might be two executive vice-presidents in a global corporation who are “neck and neck” in the race to be the next CEO. The succession planning position of these two individuals in relation to the position of all the other vice-presidents who are not in the running for CEO is the same.

In the context of Formula 1 racing, there might be two drivers who are vying closely for the lion share of championship points (points are awarded for each racing based on final position; the driver with the most points at the end of the season wins the championship). These two drivers would be considered structurally equivalent if, in a given race, they had lost to, and beaten, the same other drivers the same number of times earlier in the season.

The context of Formula 1 racing also helped eliminate other explanatory factors for conflict. For example, spatial considerations — competing vice-presidents whose offices are next to each other — could exacerbate conflict. Personality traits could also play a factor: someone prone to conflict could seek out the other individual thus increasing the chances of conflict. Both of these factors do not apply in Formula 1 racing because racers generally do their best place themselves near the top of the starting grid — rather than next to someone they wish to intimidate.

The results of the analysis confirmed that competition between structurally equivalent pairs of drivers was more likely to lead to conflict than competition between non-structurally equivalent pairs. The analysis also identified two important factors that increased the negative impact of structural equivalence: the similarity of ages between the competing individuals; and the strength of the performances of the individuals (conflict arising from equal status was more common among stronger performers).

Another important factor was the stability of the competitive network — in other words, whether the status of the individuals in the network was stable rather than volatile (in the term of the researchers, whether the structure of the network had “congealed”). Thus, conflict between two drivers was more likely to erupt toward the end of the racing season, when the placement of the drivers in the competitive standings were more set, than in the beginning of the season.

The final factor that exacerbated conflict between structurally equivalent pairs was whether the drivers felt safe. In dangerous conditions, such as in poor weather, the conflict abated, no doubt because attacking another driver in such conditions could put the other driver’s life in jeopardy and his own reputation at risk.

BUSINESS APPLICATION

While the Formula 1 context may seem specific, the competitive relationships between the drivers are very similar to the type of competitive relationships one finds in the networks of the business world.

Antagonisms will rise when the status between two individuals is ambiguous. Leaders would do well to be aware that the longer two individuals are in direct competition with each other without a clear “winner,” the more likely the competition could devolve into outright conflict.

This study also reveals that emotions related to past encounters can increase the conflict between two individuals. In the Formula 1 season, past encounters (i.e., the previous races) are front and centre as they contribute the points toward the championship. In the world of business, past encounters may not be so evident. To continue with the example of two structurally equivalent individuals vying for a promotion, if the two individuals had previously competed against each other for a promotion, emotions might run higher and lead to unproductive or dangerous conflict.

Leaders should carefully study all the exacerbating factors revealed in this research and ask themselves: is there a potentially dangerous conflict brewing between two individuals in your organization?

FURTHER READING

Henning Piezunkas profile at INSEAD Wonjae Lees profile at Graduate School of Culture Technology, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology Matthew Bothners profile at European School of Management and Technology INSEAD Executive Education profile at IEDP

REFERENCES

Escalation of Competition Into Conflict in Competitive Networks of Formula One Drivers. Henning Piezunka, Wonjae Lee, Richard Haynes & Matthew S. Bothner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (April 2018).