Bad Framing Leads to Bad Decisions and Bad (Even Fatal) Actions

This is one of our free-to-access content pieces. To gain access to all Ideas for Leaders content please Log In Here or if you are not already a Subscriber then Subscribe Here.

Decision makers must frame or ‘make sense’ of events and situations, and then make their decisions accordingly. A groundbreaking analysis of an innocent civilian’s tragic shooting by anti-terrorist police reveals how groups of individuals commit, through the interaction of communication, emotions and material cues, to a single, common frame — in this case an erroneous frame. It is a cautionary tale for leaders and other decision makers, exposing how errors or assumptions can cascade into a complete misunderstanding of situations.

To make decisions, leaders must understand, to use the vernacular, ‘what is happening’. They must make sense of the events and situations that impact their areas of responsibility; this sense-making not only involves the past and present, but also the future: what is likely to happen.

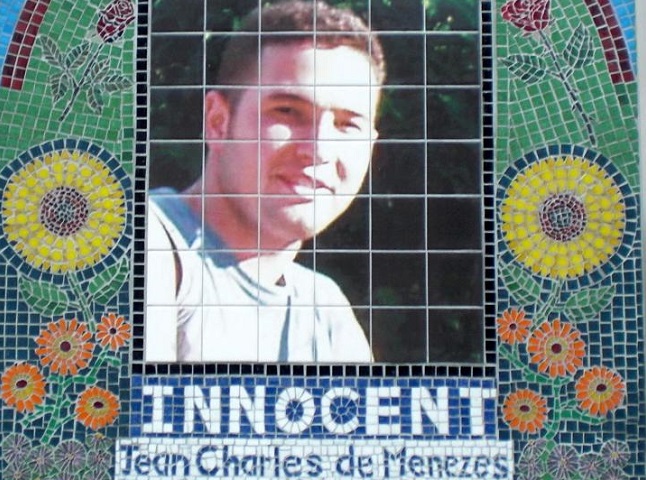

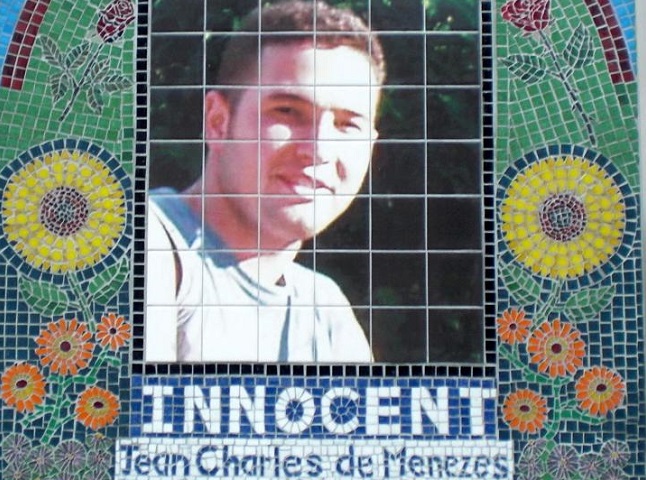

In July of 2005, an innocent man commuting to work was killed by police in a tube (subway) station in London. The shooting happened one day after four terrorists had attempted to set off bombs on tube trains, and two weeks after terrorists had successfully set off bombs in the London tube, killing 52 commuters.

A detailed analysis of all the events leading to the killing of Jean Charles de Menezes (available through the material offered as evidence in the subsequent inquest) reveals the process by which communication (the language used), emotions and material cues (such as the surroundings in which events took place and the actions of the suspect) combined to create a frame for the situation at hand.

Here are some examples:

From this detailed analysis, the researchers developed a process model that explains how a group of people can commit to a common frame that is created and reinforced over the course of events. The first step is communicative grounding. Language sets the initial frame, and the repetition of the language among those involve continue to reinforce the frame. The second step is emotional contagion. Emotions originally aroused spread to all members of the group. Finally, there is material anchoring. Perceived material cues are used to ‘anchor’ the conceptualization created through language and emotions.

Thus, the firearms team were told by the control team that they were pursuing a terrorist (communicative grounding); assigned to perform an armed intervention the team’s emotions ran high as they desperately rushed the crowded tube station trying to get to the terrorist (emotional contagion); when they see the suspect they note that his jacket is “bulky,” indicating that he was carrying a bomb (material cue — in fact, it was an ordinary denim jacket, unzipped).

The tragic killing of Jean Charles de Menezes occurred because a group of highly trained professionals became so committed to a specific frame — that de Menezes was a terrorist on a mission — that they could not consider an alternate frame, which happened to be the truth: that de Menezes was a commuter on his way to work. Business decisions are also based on a certain framing of events and situations. This tragedy is a cautionary tale for leaders in how they frame situations for others — or how others may be framing situations for them.

Leaders must pay close attention to the words and expressions they use; they must also be aware of emotions, and how those emotions may be defining their own reactions or influencing the actions of others in the organization. As the study shows, once language choices and emotions have established a certain frame, perceived material cues will only reinforce that frame — even if the frame is erroneous. The outcome may not be as tragic as the shooting of de Menezes. Nevertheless, an organization that has completely mischaracterized situations its business environment is destined for significant operational and strategic failures.

Ideas for Leaders is a free-to-access site. If you enjoy our content and find it valuable, please consider subscribing to our Developing Leaders Quarterly publication, this presents academic, business and consultant perspectives on leadership issues in a beautifully produced, small volume delivered to your desk four times a year.

For the less than the price of a coffee a week you can read over 650 summaries of research that cost universities over $1 billion to produce.

Use our Ideas to:

Speak to us on how else you can leverage this content to benefit your organization. info@ideasforleaders.com